Lyndon B. Johnson: The “Great Society” Civil Rights President

By Max Eternity

There’s no excuse for the Vietnam War. It was President Dwight D. Eisenhower who started it. The war was then escalated by President John F. Kennedy. And after Kennedy’s assassination, President Lyndon B. Johnson escalated again and continued on with the war, which by then had become very unpopular. Nevertheless, President Richard Nixon not only continued the war, but also did a lot of other unsavory and illegal things leading to his being prematurely forced from office.

It would be his successor, President Gerald Ford, who would be wise enough to finally end the Vietnam War. And Ford’s successor, President Jimmy Carter, is the last and only anti-war president since.

But somehow, in spite of all the presidents responsible for the Vietnam War, it is Johnson who seems most remembered and blamed for it. This inglorious distinction, in spite of Johnson being the president responsible for creating our modern day safety net, which includes highly successful programs like Head Start and the Federal Work Study Program through the creation of the Office of Economic Opportunity, an agency that greatly benefited the education and welfare of both the young and old, while also assuring justice and equality for American Indians and African Americans.

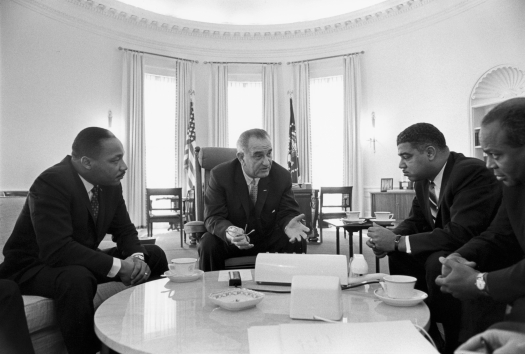

In 1964—the same year that Johnson would sign major civil rights legislation—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. shared his thoughts on Johnson. Of which parts were republished in a 2015 article at Time Magazine, what follows is an excerpt from Dr. King’s comments on meeting Johnson while he was Vice President:

I had been fortunate enough to meet Lyndon Johnson during his tenure as Vice President. He was not then a presidential aspirant and was searching for his role under a man who not only had a four-year term to complete but was confidently expected to serve out yet another term as Chief Executive. Therefore, the essential issues were easier to reach and were unclouded by political considerations.

His approach to the problem of civil rights was not identical with mine—nor had I expected it to be. Yet his careful practicality was, nonetheless, clearly no mask to conceal indifference. His emotional and intellectual involvement was genuine and devoid of adornment. It was conspicuous that he was searching for a solution to a problem he knew to be a major shortcoming in American life …

And regarding when Johnson became president, King had this to say:

Today the dimensions of Johnson’s leadership have spread from a region to a nation. His recent expressions, public and private, indicate that he has a comprehensive grasp of contemporary problems. He has seen that poverty and unemployment are grave and growing catastrophes, and he is aware that those caught most fiercely in the grip of this economic holocaust are Negroes. Therefore, he has set the twin goal of a battle against discrimination within the war against poverty.

Additionally, a 2001 essay about Johnson’s War on Poverty, published at Native American Netroots, gives insight as to how Johnson’s policies brought a sense of dignity and enfranchisement to American Indians.

In 1964, the poorest groups in the United States were Indians living on Indian reservations, a fact that had been true throughout the twentieth century and continues to be true today. On the reservations, economic development was controlled-planned, administered, and evaluated-by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). With the creation of the Office of Economic Opportunity, the BIA no longer had a monopoly on the economic future of the tribes. Tribes were eligible for funding for youth programs, community action programs, and other programs. Indian tribes and organizations participated in these programs along with other economically disadvantaged groups. Unlike the earlier BIA programs, these new programs emphasized the need for local involvement at all levels. Soon nearly every tribe in the United States was involved in the War on Poverty and local Indian people, not the BIA, were planning and running the programs. In other words, the War on Poverty provided tribal people with political empowerment.

Johnson cared deeply for the working poor and the middle class. He was a strong advocate for public transportation and a fierce defender of the environment. In fact, the many government programs created by the Johnson Administration were so effective they have since become both normalized and taken for granted.

For instance, under President Johnson’s leadership Medicare and Medicaid were created. So was the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (PBS) and The National Endowment for the Arts, as well as The National Endowment for the Humanities.

And under Johnson’s guidance, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) created the 911 emergency system.

But that’s not all. Johnson also signed into legislation the Clean Air Act of 1963, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Urban Mass Transportation Act of 1964, the Wilderness Act, the Food Stamp Act (SNAP/EBT) of 1964, Housing Act of 1964, the Social Security Act of 1965, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), and the Gun Control Act of 1968.

All of these programs and so much more were part of what Johnson called the Great Society. In a 1964 speech at the University of Michigan, he gave a speech about his vision for building the Great Society:

The purpose of protecting the life of our Nation and preserving the liberty of our citizens is to pursue the happiness of our people. Our success in that pursuit is the test of our success as a Nation.

Your imagination, your initiative, and your indignation will determine whether we build a society where progress is the servant of our needs, or a society where old values and new visions are buried under unbridled growth. For in your time we have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society.

Further in his speech, Johnson articulates the pillars of the Great Society, saying:

The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time. But that is just the beginning.

The Great Society is a place where every child can find knowledge to enrich his mind and to enlarge his talents. It is a place where leisure is a welcome chance to build and reflect, not a feared cause of boredom and restlessness. It is a place where the city of man serves not only the needs of the body and the demands of commerce but the desire for beauty and the hunger for community.

It is a place where man can renew contact with nature. It is a place which honors creation for its own sake and for what it adds to the understanding of the race. It is a place where men are more concerned with the quality of their goals than the quantity of their goods.

The end of Johnson’s speech could easily be confused as speech written by Dr. King, when he extols the virtues of justice and equality, asking with vigor:

So, will you join in the battle to give every citizen the full equality which God enjoins and the law requires, whatever his belief, or race, or the color of his skin

Will you join in the battle to give every citizen an escape from the crushing weight of poverty?

Will you join in the battle to make it possible for all nations to live in enduring peace–as neighbors and not as mortal enemies?

Will you join in the battle to build the Great Society, to prove that our material progress is only the foundation on which we will build a richer life of mind and spirit?

Johnson was indeed the Great Society president. His record reflects his word and he should be remembered and held high for his deep compassion and commitment to extending essential services to all, for granting legal rights to those with disabilities, while also building up public transportation, defending the environment, protecting the rights of immigrants, and for his extraordinary civil rights record that still rings true today.

You must be logged in to post a comment.